The next stop on our trek farther west was a small state park known for ancient cave paintings and natural water retaining pits in granite hills. The hills formed 30 some odd million years ago as an igneous intrusion (blobs of magma that formed under ground and eventually became exposed through erosion), and the same continued erosion created the hollows on the surface known as hueco’s to the Spanish. The first traces of human presence through pictographs and artifacts dates back to the Paleo Indians and has maintained being a sacred site to various groups through history to today’s Native people. The place definitely has a “vibe.”

Because of the fragile ecosystem and history in the area, access is closely restricted. Almost half the park isn’t accessible unless with a guide. Weeks before our arrival, I booked our campsite and daily passes over the phone with an onsite park ranger. Once there, we were required to watch an orientation video detailing the rules of the park. Each day before hiking in the self guided area, we had to check-in at the headquarters, check out once we were done and then were to remain at our assigned campsite until the next day.

The campsites are large with awesome awnings over the picnic tables and large tent pads. If there is a next time, I scouted some even cooler sites that back up to the hill and cozy up under boulders! We spent the rest of the evening setting up camp and managed to eat dinner before the rain rolled back in.

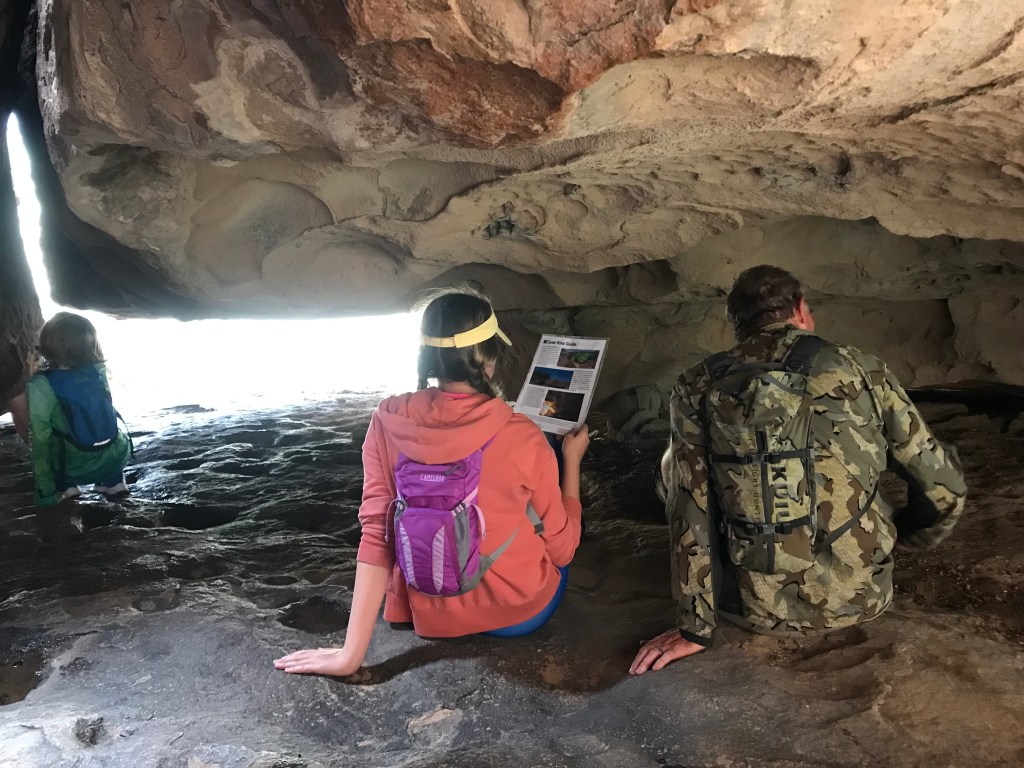

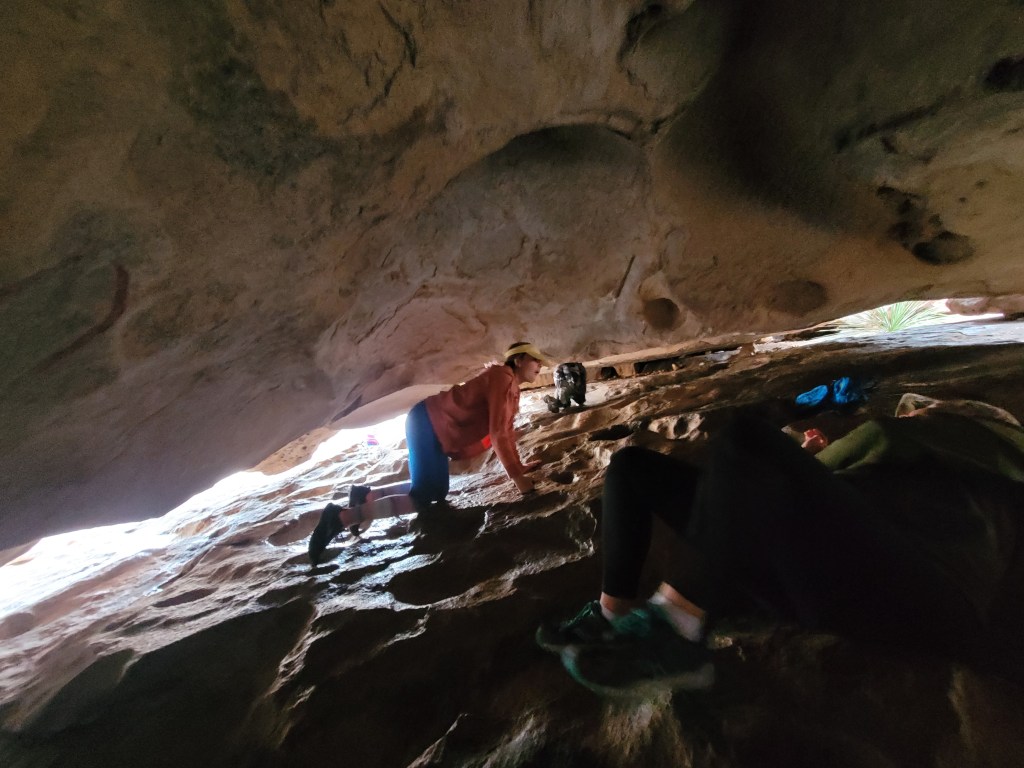

The next day, we explored the open access area. When we checked in, we were offered a cryptic “map” that would lead us to some of the more popular pictographs in the park. It took effort on everyone’s part to cipher the riddles, but we did eventually make it to the cave and checked out hueco’s along the way.

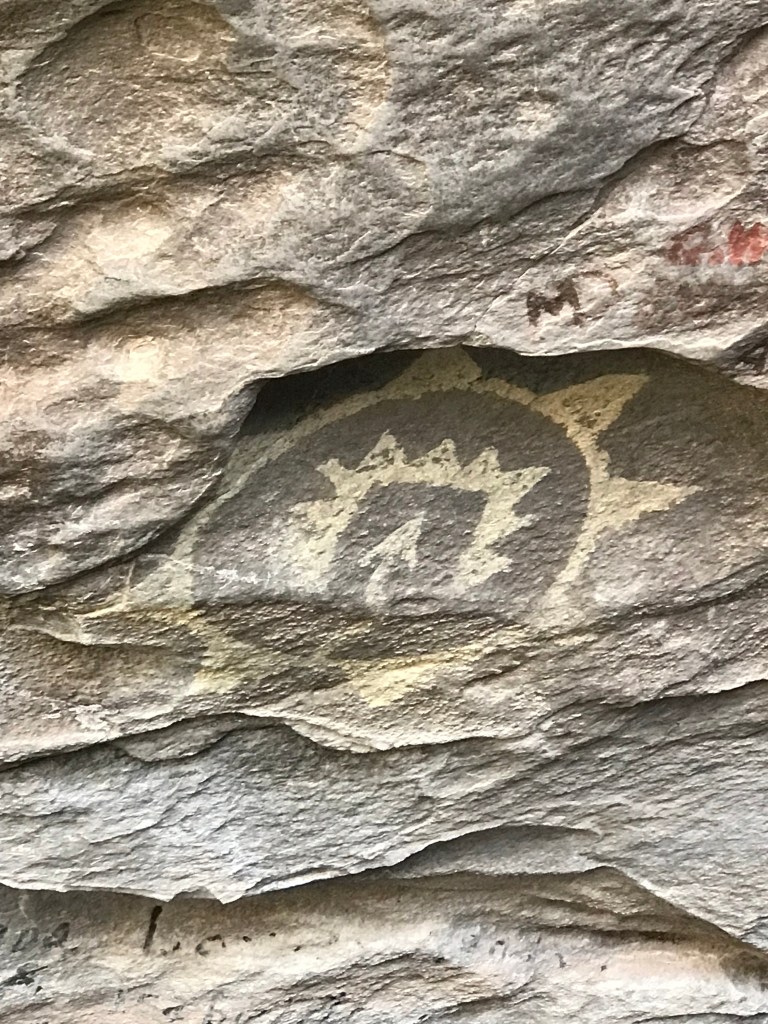

Once in the cave we forgot about the frustrations of the map and literally laid there in awe of the “masks.” The people of Jornada Mongollon group are credited with this art. They were the first to create a village at the base of the hills ceasing their ancestors nomadic ways. They managed close to 700 years there before series of drought made the huecos unsustainable. We spent some time picking out favorites and discussing who or what they were representing.

That evening we managed to get through dinner and Dad made some adjustments to his tent in time for it to pour again. I guess we can be grateful it wasn’t coming during the day.

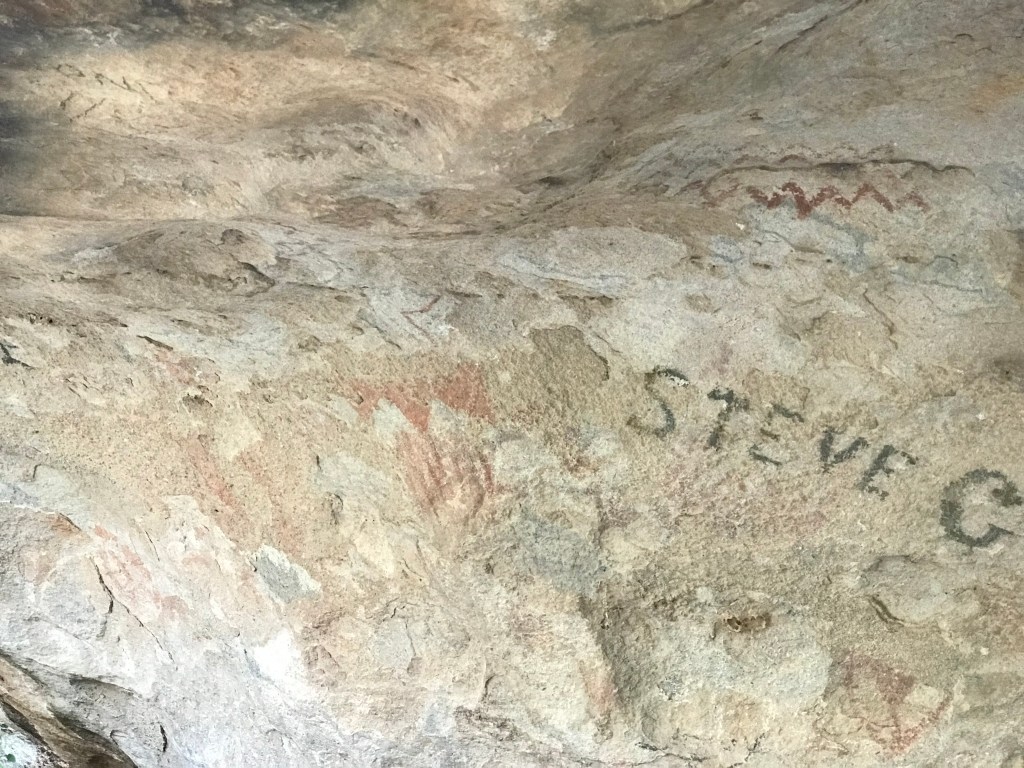

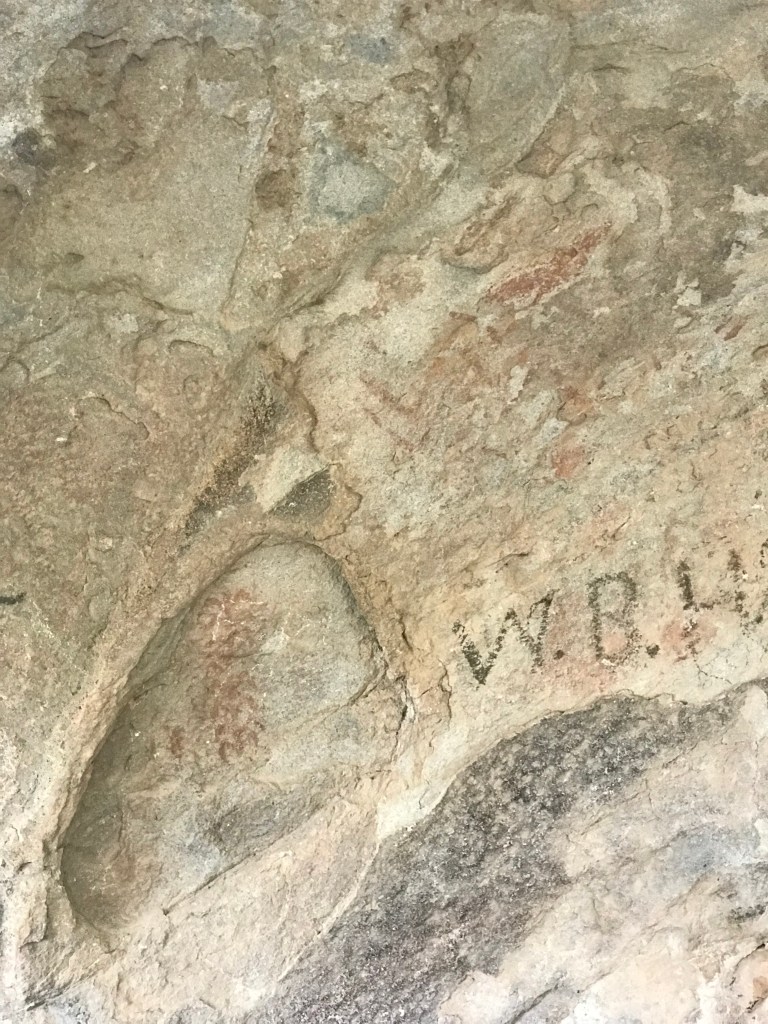

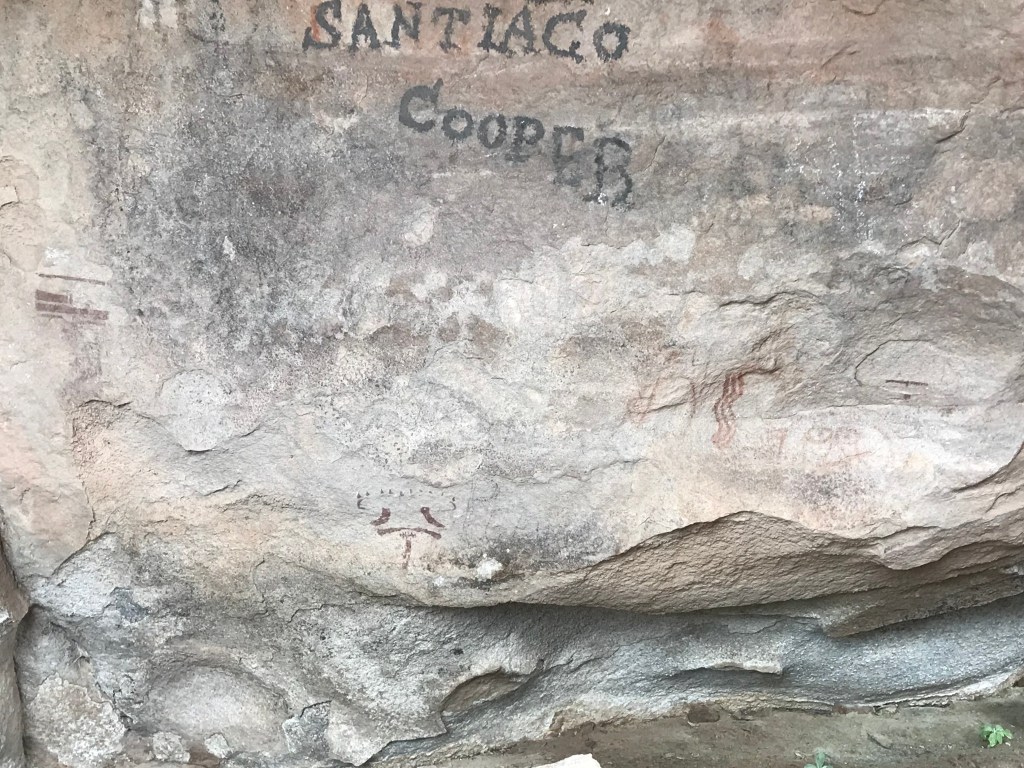

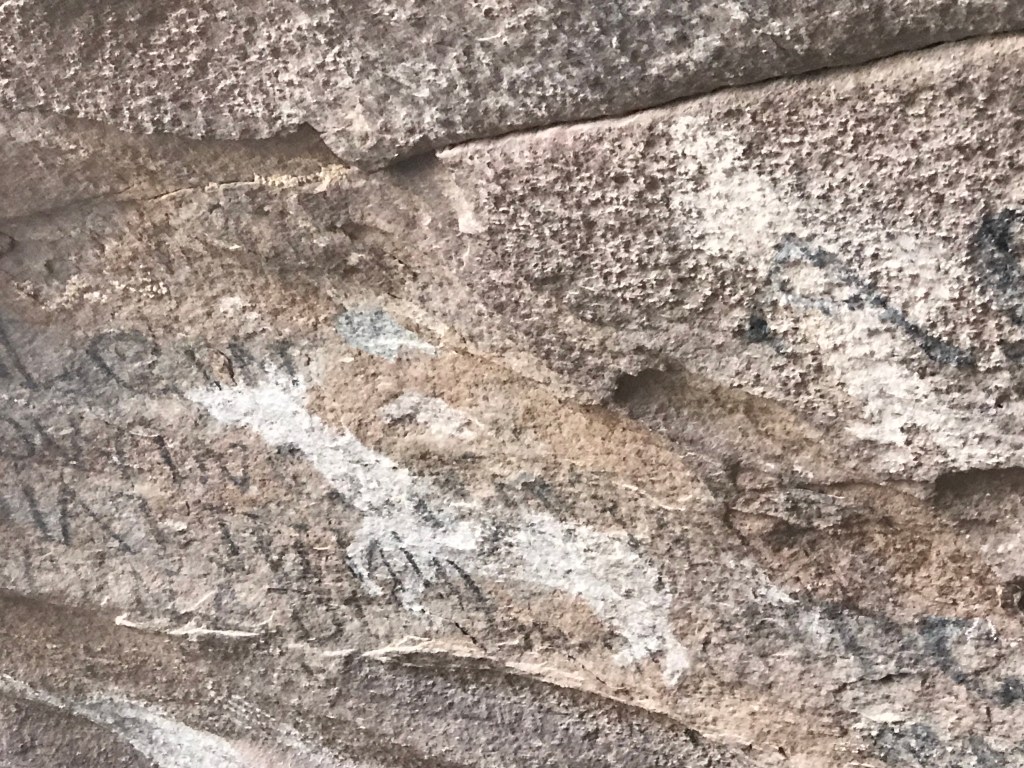

We met our tour guide the next morning and set off to see the exclusive pictograph sites. We started at an area with Apache art work from the 1600s that also displayed “historic graffiti” from the mid 1800s scrawled over much of it. The area was used as a stagecoach station during that time and people got bored, I guess. Our guide explained that while much restoration and laser removal of graffiti has taken place in the park since the 90s, anything over 50 years old is considered historic and must remain untouched. Even if it is destructive to previous history.

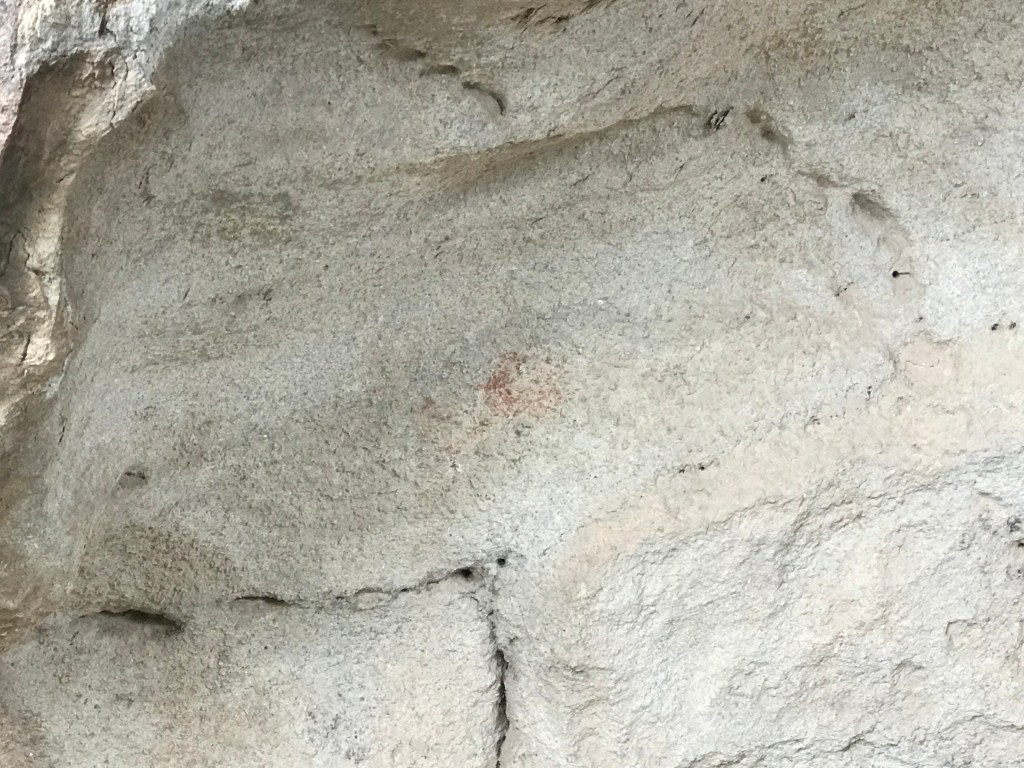

After that location, we got to see some evidence of Desert Archaic people art dating back to over 2 million years ago! Its shocking any imagery is left, but the combination of minerals used to make the paint and a weathering effect doing the opposite of what you would think, some images remain. One could ponder a long time what exactly they were trying to depict, but the truly astonishing image is a hand print! When our guide pointed it out, no one could see it other than some color on the rock. But, through the powers of technology in a handy dandy app on her phone that detected pigmentation….bam! Caveperson handprint! Wow!

On the way to the last location, we passed some areas where a ranching operation owned the area starting in 1890s and made “improvements” for water retention. El Paso county took over the land on behalf of historical societies in 1956 after the family put the property on the market. After a decade of debate on who the land should belong to, El Paso gave it to TPWD and it became a state park. Local Native tribes still have special access to the sacred land for ritual practices and the last area we went to is still in use.

Our final stop was tucked under a serene outcrop alongside a small pool of water. The outcrop displayed the most modern art work from the Tigua Tribe also known as The Pueblos. They are still an active culture in the area and practice coming of age ceremonies on the site. But their ancestry dates back to the 1600s. Part of their history entailed scouting and guiding Spaniards. One of the images on the rock that they commonly use represents a “way home” and they would often draw it while travelling. That one became my favorite of them all 🙂

Our last night was rough. The rain blew in shortly after we returned to camp that afternoon and behind the rain the wind pounded the rest of the night. I was worried about the canvas most of the night and it was shocking Dad had a tent left. We packed up quickly that following morning feeling pretty worn out and water logged.

Weather aside, this park is in my top 5! The work that TPWD is doing to preserve it is commendable. They are still having to remove graffiti, but at least their protocols are making it easier to catch and prosecute the trespassers. Beyond all the astounding history and geology, there truly is something sacred feeling about the entire area. I guess millions of years of people being drawn to it speaks for itself.

-Lindsay

This was a good read.

Here is what I think

What an incredible experience! It’s amazing to hear about the history and preservation efforts of this state park. Thank you for sharing your adventure with us.

Ely Shemer

LikeLike

Glad you enjoyed the post! Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person